“AThe concept of ”rt" is used in French, English and Latin (artem) languages for the first time in the 13th century and was defined in the sense of human prowess and skill. This term is derived from the Latin ars or artem root, etymologically derived from the Greek techne is related to the concept of "skill" (Tatarkiewicz, 1980). Both roots refer to human actions based on mastery, method and the capacity for creative production (Tatarkiewicz, 1980). The seven free arts included in the medieval university curriculum - thetrivium (grammar, rhetoric, logic) and quadrivium (arithmetic, geometry, music, astronomy)-are the areas where these skills were institutionalized. Individuals who received education in these disciplines and exhibited intellectual or applied skills were defined as “artisans”, that is, both intellectual and manual labor-based productions were considered under the umbrella of “artifex” (Eco, 1989). Over time, however, the need to distinguish between creative activities based on intellectual, imaginative or aesthetic concerns and skilled manual labor for utility becomes apparent, and this practical need also brings about a conceptual division: Art and Craft.

By the 18th century, art was used to refer to fields such as literature, architecture, sculpture, sculpture, dance, theater and opera, while craft was used to refer to the work associated with skilled craftsmanship in everyday life (Shiner, 2020). In this differentiation, Immanuel Kant's immortal work “A Critique of Pure Reason” (Critique of Judgment, 1790), the distinction between “free art” and “mechanical art” can be said to be decisive. For according to Kant, the true value of art is not based on utility, but on freedom and imagination, which makes the concept of “creativity” the hallmark of the artist (Kant, 2022 [1790]). Before the eighteenth century, the terms “art” and “craft” were used interchangeably and considered synonymous, while the terms “artist” and “craftsman” were considered equivalent. Indeed, the word artist is used not only for painters and composers, but also for shoemakers, carriage wheel makers, alchemists and art students. By the end of the 18th century, however, “artist” was the creator of beautiful works of art, while “craftsman” described only those who produced useful things and had skills.

At this point, port cities have historically stood out not only as centers of trade and logistics, but also of cultural exchange, aesthetic pluralism and creativity, and thus of arts and crafts. Port cities function as contact zones where different cultural, economic and social groups meet and interact and hybrid identities emerge (Hannerz, 1996; Braudel, 2021). It was not only goods that were transported over sea routes, but also ideas, styles, techniques and aesthetics. In this context, the interdisciplinary interaction inherent in creative production, the encounter with difference, and the “open systems” that foster innovation coincide with the character of port cities.

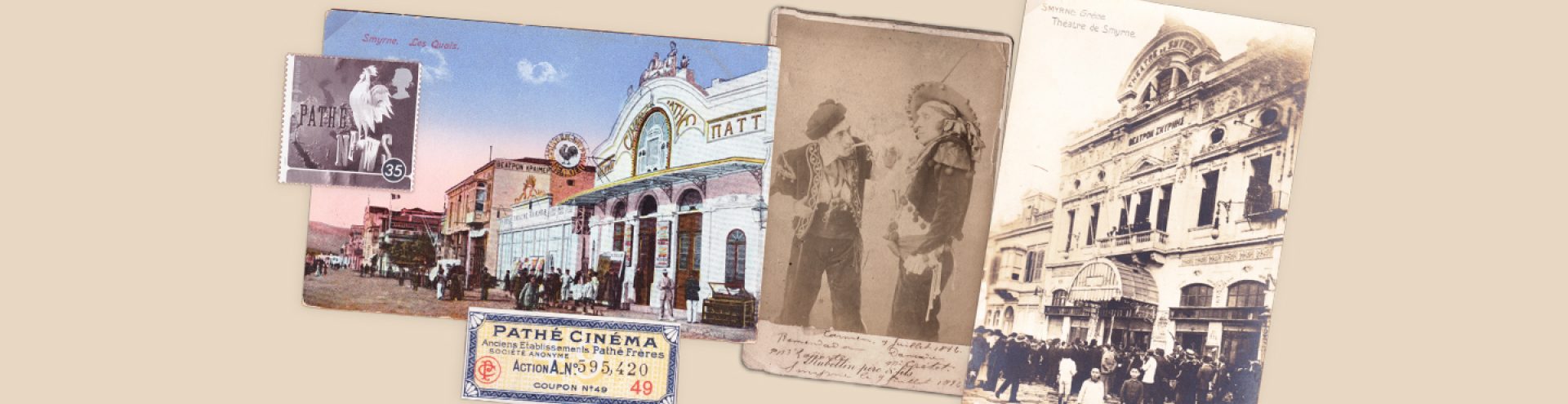

İzmir is a living example of these interactions due to its historical position in the Mediterranean geography. It has been the port of many civilizations from antiquity to the Ottoman Empire and from the Republic to the present day, and has harbored a cultural fabric shaped jointly by Levantine, Jewish, Armenian, Greek and Turkish populations. The most important feature that distinguishes İzmir from other port cities is this harmonious cultural fabric formed by people of different nationalities. What established this harmonious environment was undoubtedly trade. The magnitude of the development in İzmir's commercial life can be seen in the fact that the number of inns increased from 60 in 1640 to 82 in just thirty years. Indeed, inns were at the heart of commercial life in the Ottoman Empire, and by exhibiting the traditional ’arasta’ structure in Izmir, the Kemeraltı district was transformed into an area where stonemasons, marble makers, kavafs and weighbridges were located. artisan island They transform it. In the 18th and 19th centuries, İzmir experienced its golden age and became the most important port city of the Eastern Mediterranean, and the leading export port of the Ottoman Empire. A privileged province of the Ottoman Empire in terms of private property, Izmir was an intellectual and cultural center that hosted 17 consulates in the 1850s and was served by Austrian, French, British, German, Russian, Greek, Greek and Italian post offices in addition to the Ottoman post office. In addition to these structures that facilitate and nourish trade, there is an infrastructure that supports creative gatherings such as cafes, inns, arcades and theaters that make the city socially and culturally attractive. In the 19th century, Boğos Tatikyan founded Izmir's first photography house, which paved the way for a creative concentration in Izmir in the following years through new photography houses (Foto Gagin, Hamza Rüstem Fotoğrafhanesi, Yıldız Fotoğrafhanesi) and photographers. According to the 1890 Aydın Salnamesi, there are 35 casinos, 2 theaters and 3 clubs in İzmir. On the other hand, İzmir also has distinctive characteristics in terms of printed publications. In the 19th century, İzmir was the Anatolian city where the first French newspaper (Le Smyrneen, 1824) and the first Greek newspaper (Filos ton Neon, 1831) in the history of the Ottoman press were published. In the early years of the 20th century, İzmir was the only city where 17 different newspapers were published in French, Armenian, Greek and Hebrew in addition to Turkish. This cosmopolitan structure made it possible for İzmir to become not only a commercial port but also a port of culture and creative production (Keyder, 2007; Eldem, 2010).

Tracing the historical and conceptual foundations of creativity makes it possible to develop a deeper understanding of the spaces where creativity is born, develops and takes root. As in the case of Izmir, port cities are open systems that allow for the multifaceted circulation not only of goods but also of knowledge, culture and aesthetic forms. İzmir's rich historical layers are characterized by a creative coexistence that extends from craftsmanship to fine arts, from printing to multilingual publishing, from inns to post offices, from performing arts to public meeting spaces. This structure shaped not only the economic but also the cultural and artistic capacity of the city. Here, creativity is not only an individual talent or a modern category; it manifests as a collective practice that has permeated the fabric of urban life throughout history, fed by geography, intertwined with multiculturalism and production.

Aydın Salnamesi, 1890/91 (pp.547-548)

Braudel, F. (2021). “The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Period of Felipe II-1”, Trans. Mehmet Ali Kılıçbay, Doğubatı Publications.

Eco, U. (1989). The Middle Ages and the Birth of the Artist. In Art and Beauty in the Middle Ages. Yale University Press.

Eldem, E. (2010). “Istanbul: From Imperial to Peripheral Port City”. In The City in the Ottoman Empire: Migration and the Making of Urban Modernity. Routledge.

Hannerz, U. (1996). Transnational Connections: Culture, People, Places. Routledge.

Kant, I. (2022 [1790]). “Critique of Pure Reason”. Trans. Naci Pektas, Gece Kitaplığı.

Keyder, Ç. (2007). “Istanbul: Between Global and Local”. Metis Publications.

Shiner, L. (2020). “The Invention of Art - A History of Culture”. Translation. İsmail Türkmen, Ayrıntı Publications

Tatarkiewicz, W. (1980). “A History of Six Ideas: An Essay in Aesthetics”. Springer Publications.