The inns that adorn the caravan routes of Anatolia have witnessed the stories carried by travelers, merchants and different cultures for centuries. The inns ensured the continuity of trade along the caravan routes and provided safe accommodation for travelers. When the Ottoman Empire emerged on the stage of history, it continued to develop this trade tradition and enriched the trade routes in the vast and fertile geography it dominated with range inns and the city centers with inner-city inns that kept the pulse of commercial life.

The emergence of inner-city inns in İzmir, a port city, began with the city's accession to the Ottoman Empire in 1426. In the course of the harbor's evolution over time, İzmir becomes one of the most prominent cities on the Aegean coast with its commercial identity, fed by both the developments in its surroundings and its own internal dynamics. In 1634, the French traveler Jean-Baptiste Tavernier wrote about Izmir: “Smyrna is the most famous of all the cities of the Levant in terms of sea and land trade; it is the most recognized market for all goods going from Europe to Asia and vice versa.” "Izmir's commercial vibrancy". This commercial vitality, highlighted in Tavernier's words, revealed the increasing strategic value of İzmir. Indeed, İzmir, which was used as a supply and transshipment point during the Cretan War of 1645-69, developed significantly after this period with the great investments of Köprülüzâde Fazlı Ahmet Pasha. During these years, when even the paving stones were renewed, the city's commercial infrastructure was strengthened with the magnificent Grand Vizier Inn. The acceleration of trade in the city and the increase in investments directly paved the way for the proliferation of inns. In the same century, the city also witnessed new beginnings; due to the wars and heavy taxes in the eastern ports, consulates and balyos turned their attention to İzmir and İstanbul. The consulates in the city played an important role in increasing the commercial activities of European merchants and the settlement of Levantines in İzmir.

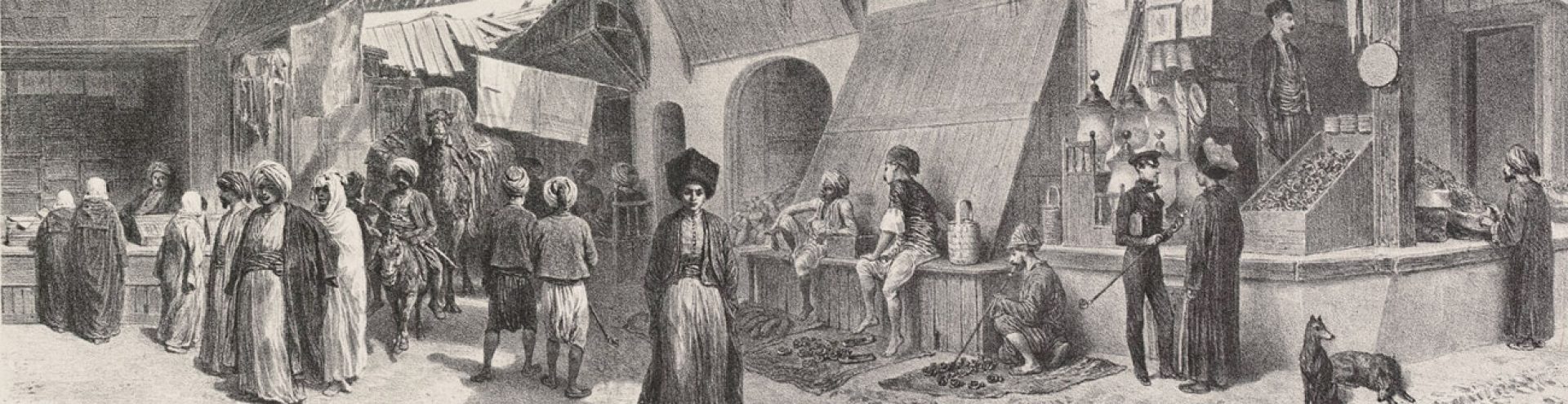

Along with the inns, bazaars, bedestens, arastas and rows of shops covered a large part of the city, and the diversity of commercial life was reflected in the abundance of imported and exported goods. While many valuable products such as acorns, raisins, raw cotton, olive oil, opium, wheat, silk, boxwood, wine, carpets and fabrics were exported from İzmir, goods such as sugar, paper, lead, needles, firearms, oil, textiles and Venetian glass were imported. All this activity transformed İzmir into a trade gateway connecting Europe and the Mediterranean with the East, and made it an important route, especially for the transportation of silk to the West. In the mid-17th century, when the trade of the Eastern Mediterranean and the islands was diverted to the coasts of Izmir, this commercial activity in the city further increased, and in the mid-19th century, it took on a new dimension with the impact of industrialization.

Izmir's inns adapted to the changing face of the city over time, assuming different functions according to the needs of each period and renewing their architecture accordingly. Following in the footsteps of the Ottoman inner-city inns, these inns enveloped Izmir like a shroud in different forms, such as courtyard inns, arasta-like gated inns, and slender ferhanes spread over long parcels on the coast. The inns have established a close connection with their neighborhoods, giving their names to the streets their facades open onto and reflecting their function or the identity of their owners in their names.

If we listen to the historical adventure of Izmir's inns from the beginning, what kind of a journey would it tell us in the memory of the city?

The beginning of the organization of inns within the commercial fabric of Izmir dates back to the 15th century. At that time, caravans reaching the borders of the city were first checked at Mezarlıkbaşı before they mingled with the crowds on the streets, and in the following years, in the areas where Armenians stayed. This order continued until the trade load carried to the city began to push the limits of these places.

In the 16th century, Izmir began to gain a city identity, and with the increase in trade and the proliferation of caravans, the control point shifted to the Kervan Bridge area. From the late 16th century onwards, the city was accessed via two routes. The first route follows the curves of Kemer and Tilkilik Streets and leads to Ali Paşa Street, which leads to Demir Hanı. Here, the open areas where the caravans used to gather disappeared in the shadow of inns such as Bölükbaşı, Deve and İmamoğlu. Thus, a new road appears for the caravan and the entrance to the city shifts to the second route, the new road that would become Osmaniye Street. Deveci passes through the Kervan Bridge and reaches the Büyük Vezir Inn via this street. Over time, Osmaniye Street is lined with foundation inns and becomes a route of wealth and vitality. Important inns for İzmir, such as Büyük Karaosmanoğlu Han, Mirkelamoğlu Han and Selvili Han, were lined up on this street, where people of different nationalities and a variety of goods flowed. Although the inns were under the supervision of the chief architect, they could not develop in a planned order on a city scale; the original organic street texture of the Muslim neighborhoods also manifested itself on this street.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the silhouette of Izmir seen from the sea begins to take on the identity of a port city with the influence of trade. In this period, Büyük Vezir Han and Çakı and Çuha Bedestens rise on the coastal line to carry the increasing commercial weight and set an example of planned design for İzmir. It is clear that the Büyük Vezir Hanı, which stands like a gate at the entrance of Frenk Street at the point where caravans reach the harbor, is located here as a result of a strategic decision. Hans with courtyards generally rose in the city during this period, sometimes with pools and fountains in their courtyards. Richard Chandler, who visited Izmir in 1764-65, reports his observations on the spatial character and daily functioning of the inns as follows:

“The inns are square or rectangular in shape, and many of them have a pool in the center. The upper floor consists of rooms opening onto an open gallery and often a small masjid. Downstairs are camels, mules and horses with their loads. When you arrive at the inn, a servant will dust the room, spread the mattress, the only furniture, on the floor and leave you alone. The doors close at sunset.”

These sentences give clues as to the scenes that the inns witnessed in daily life. Producers from the surrounding villages delivered their goods to brokers or criers at the inns, and the products reached the hands of the public. Clerks recorded all sales. People spent time in the coffee houses and restaurants on the street-facing sides of the inns. In addition to shopping, various issues are discussed here, news is disseminated throughout the city from the inns; thus, the space, with all its actors, turns into a social meeting place beyond commerce.

While this vibrant life in the inns continues, the physical fabric of Izmir is also in flux, and from the late 18th century onwards, significant changes are evident around the harbor. By this time, the inns lining the inner harbor were witnesses to the fate of the harbor, which continued to fill up. According to Richard Chandler in 1764-65, in rainy weather the harbor was almost “a big pool filling up in the middle of the city” appearance. In such a landscape, new inns began to rise above the inner harbor before the end of the 18th century.

Wolfgang Müller-Wiener's plan of the harbor and bazaar area of Izmir. Mosques (dotted), baths (cross-hatched), public buildings (hatched) and hans (with catalog numbers and - as far as possible - a schematic floor plan).

Izmir Bazaar Book, p. 96

The work on this plan was done by graphic designer Orçun Andıç. This work is also included in the maps section of the Izmir Bazaar Book.

By the 19th century, Izmir's commercial life underwent a radical change. In the second half of the 19th century, the Aydın-İzmir and İzmir-Kasaba Railway Lines and the İzmir Quay are carved into the face of the city. Thus, the railroads take over the work of the caravans and provide much faster transportation. By the end of the 19th century, the old-time caravan traffic in Izmir had almost disappeared. The ferhanes on the coast lost their connection to the sea in the new layout created by the embankments built for the docks and turned into bazaars.

In the 19th century, increasing trade activity brought with it a lack of space, leading to the rise of large and small warehouse inns on landfills. These inns, most of which were simple stone structures, gave Izmir a new silhouette when viewed from the sea, along with the waterfront. While warehouse inns took shape in different parts of the city, especially on the First Kordon, the Second Kordon and the back neighborhoods of Kemeraltı, the processing of products was mostly carried out in the inns in the bazaar area. Some inns became identified with the products they stored and were known by names such as “Tütün Hanı” and “İncir Hanı”. Frenk Street and the Traditional Bazaar, the center of Izmir's public life, were differentiated according to the commercial activities of ethnic communities. While Turks predominantly operated mixed-use warehouses in the Traditional Bazaar, warehouses owned by Armenians, Greeks, Jews and Levantines were concentrated on Frenk Street and around the harbor. Towards the end of the 19th century, pioneering warehouse inns, where motorized systems were introduced and machines were used in storage and packaging processes, emerged on the commercial scene.

By the beginning of the 20th century, the caravan bridge had quietened down and Basmane continued its active days thanks to the density brought by the railway. Looking at the distribution of inns in the urban fabric during this period, Osmaniye Street was one of the prominent centers. The Mezarlıkbaşı area, which is the stop of Tilkilik Street, another route of the city, stands out especially with Menzil and Kömür Inns. As for the Bazaar Hans, Kızlarağası Hanı, Büyük Demir Hanı and Küçük Demir Hanı are among the most prominent buildings.

The inns at the end of Kemeraltı Street are mostly used by Muslims and Jews, while around the Başdurak Mosque there are Jewish houses where Jewish families live in solidarity. The term “balyos” in the names of the inns in Ali Paşa Square indicates that these buildings were used by minority groups.

In this century, when industrialization accelerated and economic balances shifted, Izmir's traditional inn fabric underwent a transformation process. Rising on the outskirts of the city, the inns were initially frequented by caravan passengers, but with the expansion of the city and the decline of caravans, they turned into housing and work spaces for low-income families, workers and small production centers. For example, Deve Han and Bölükbaşı Han, which once hosted caravans, became the living quarters of Jewish and Armenian families. Other inns such as Karaosmanoğlu, Mirkelam and Kızlarağası were taken over by companies and turned into workplaces. After the construction of the quay, the Old Ottoman Customs, Saman İskelesi and the inns on Mahmudiye Street lost their accommodation function and started to be used as workplaces for merchants who stored their goods in other inns. The hotel inns at the seafront end of Hükümet Street, with their flamboyant facades facing the street, have recently been used as accommodation for business travelers.

However, despite all these transformations, many of the inns could not survive the disasters that the city experienced. Ninety percent of the inns have been destroyed by earthquakes, fires and man-made destruction over the past centuries. Some of the inns mentioned by Evliya Çelebi could not be identified even on old maps, and with the possibility of name changes, it is understood that they were destroyed as a result of past disasters. The 1922 fire caused deep wounds in the memory of the city and completely destroyed the area north of Fevzi Paşa Boulevard.

Some of the inns that survived the fire could not withstand the increasing commercial pressure in the 20th century and were replaced by modern bazaars or business inns.

Only a few of the inns that played an important role in Izmir's commercial life have survived to the present day. Some of these inns have been preserved and restored in a way that reminds us of the splendor of the past, while others are waiting to return to their old times under a thick layer of dust. The few remaining inns continue a silent struggle against extinction in order to keep their last traces alive. However, this silent testimony has been made visible thanks to researchers, and Izmir's inns have continued to live on in academic studies.

Izmir's inns have been studied by many valuable researchers until today and have been recorded, including examples that have disappeared in the past:

K.Phalbos identified 96 inns, Münir Aktepe 76, Wolfgang Müller-Wiener 180, Bozkurt Ersoy recorded 103 inns excluding warehouse and hotel buildings, and Çınar Atay mentioned 202 inn buildings. Some of the inns were included in the Thomas Graves maps of 1836-1837 and Luigi Storari maps of 1854-1856; the Charles Edward Goad Plan of 1905 shows them in detail, down to the number of storeys and porticoes; and the Jacques Pervititch Plan of 1923, prepared after the fire of 1922, reveals the extinct inns. Among these studies is Wolfgang Müller-Wiener's 1982 publication Der Bazar von İzmir: Studien zur Geschichte und Gestalt des Wirtschaftszentrums einer ägäischen Handelsmetropole, published by Wolfgang Müller-Wiener in 1982, remains one of the most comprehensive studies on the memory of İzmir's bazaars and inns. This article is part of the Izmir Development Agency Cultural Publications, Izmir Bazaar: Research on the History and Architecture of the Economic Center of the Aegean Trade Metropolis has been translated into English by Emrah Dönmez, and a detailed visual design and mapping work has been carried out by the Agency's graphic designer Orçun Andıç to contribute to a better understanding of the work. As one of the most up-to-date sources on the inns of Izmir, this work contributes to researchers and has a critical importance in analyzing the city's commercial and living silhouette woven with inns.

To access the inventory of Izmir inns between the 17th and 19th centuries Click here; The works of Münir Aktepe, Wolfgang Müller-Wiener, Bozkurt Ersoy and Çınar Atay were also utilized.

Aktepe, M. M. (1971). Preliminary information about İzmir inns and bazaars. Istanbul University Faculty of Literature Journal of History, 25, 105-154.

Alpaslan, H. İ. (2015). 19th century demographic and spatial situation of Izmir. Aegean Architecture, (89), 46-49.

Atay, Ç. (2003). Closing doors Izmir hans. İzmir Metropolitan Municipality Culture Publication.

Beyru, R. (1991). Planning and zoning practices in Izmir from past to present. Aegean Architecture, (3), 41-47.

Beyru, R. (1998). A brief note on the 19th century old piers in Izmir. Aegean Architecture, 26(2), 40-41.

Beyru, R. (1998). Izmir in the 19th century: From Ottoman city to European city. Literature Publishing.

Bilsel, F. C. (2000). In the second half of the 19th century, large-scale urban projects and the metamorphosis of urban space in İzmir. Aegean Architecture, 10(4), 34-37.

Ersoy, B. (1988). Some determinations and investigations on Izmir inns. Ankara University Journal of the Faculty of Language and History-Geography, 32(1-2), 95-103.

Ersoy, B. (1991). Izmir inns. Atatürk Culture Center.

Ersoy, B. (1995). This is an obituary. Ege Architecture, (15), 47-49.

Ersoy, B. (2001). Functions of Ottoman inner-city inns. In M. Kiel, N. Landman, & H. Theunissen (Eds.), Proceedings of the 11th International Congress of Turkish Art, Utrecht, The Netherlands, August 23-28, 1999 (EJOS IV, No. 16, pp. 1-3). Netherlands Institute for Near Eastern Studies.

Ersoy, B. (n.d.). Izmir's Inns Resisting Time. Izmir Magazine. https://www.izmirdergisi.com/tr/mimari/82-izmir-in-zamana-direnen-hanlari

Gençer, C. İ. (2017). Urban transformation in 19th century İzmir and Thessaloniki: The construction of docks and harbors. Meltem Izmir Mediterranean Academy Journal, 2(1), 33-51.

Izmir Time Machine, Izmir Inns, 3D Models, https://izmirtimemachine.com/zamanyolculugu/kemeralti/hanlar/hanlar/

Müller-Wiener, W. (1982). Der Bazar von Izmir: Studien zur Geschichte und Gestalt des Wirtschaftszentrums einer ägäischen Handelsmetropole. Wasmuth.

Müller-Wiener, W. (2025). Izmir Bazaar: Studies on the History and Architecture of the Economic Center of the Aegean Trade Metropolis. (E. Dönmez, Translation). Izmir Development Agency Culture Publications. (Original publication date 1982).

Özbek, İ. E. (2021). Port and city interaction in the historical process: Izmir example. Meltem Izmir Mediterranean Academy Journal, 10(1), 5-23.