Luigi Storari is a very important but still not very prominent figure for Izmir in the 1850s. Storari was born into a wealthy and intellectual family in Ferrara, in the Emilia Romagna region of Italy in 1821. Storari studied engineering at La Sapienza University in Rome, where he not only learned the modern techniques of building bridges, waterways and buildings of the time, but also improved his knowledge of Ancient History and Archaeology by visiting and studying the ancient ruins in the city (Berkant, 2017). Storari's cultural accumulation in Rome, which was a meeting point for architects, artists and intellectuals, is analyzed in his Izmir Guide with Historical Notes published in 1857 (Berkant, 2017).Guida con Cenni Storici di Smirne) has put forward.

Cenk Berkant Archive

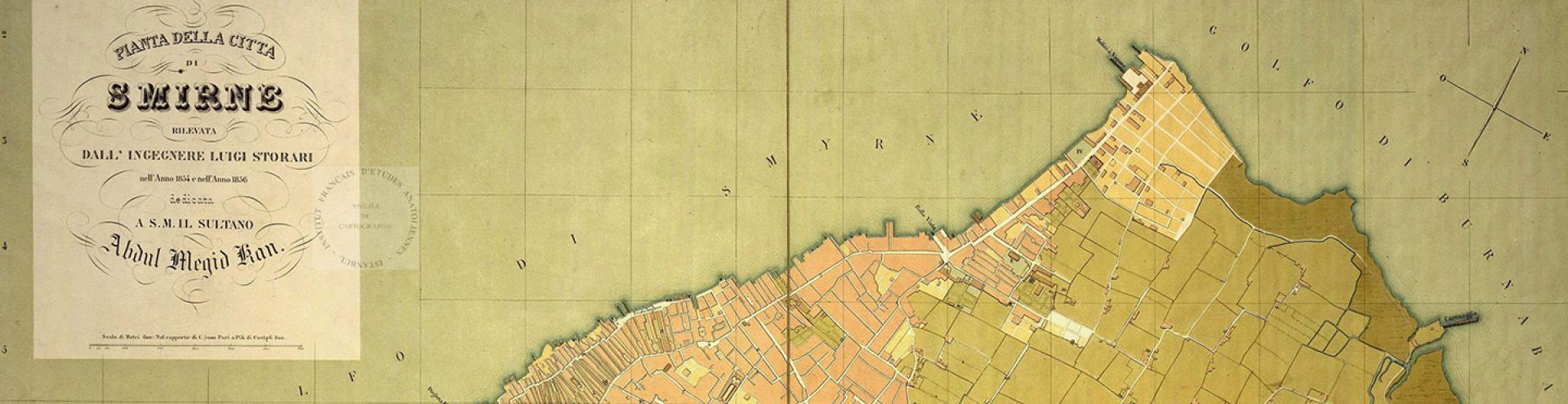

The story of Storari's arrival in Izmir is quite interesting. Luigi Storari, an engineer, had to leave Italy due to political turmoil before the Italian Union in 1861, and the Italian Immigrants Committee in Izmir (Comitato di Emigrazione ItalianaHe came to the city in 1849 through a French patronage. After settling in İzmir, he became a French protégé and was able to move more freely with this protection. From April 1, 1851 to the end of May 1854, engineer Luigi Storari worked under Ali Nihat Efendi, who was sent from Istanbul to deal with the land and real estate reform in the city (Yerasimos, 1996). With this reform, innovations such as the division of the city into four sections with a new urban organization, renaming streets and avenues, equipping them with street signs and putting numbers on buildings were introduced. During this period, Engineer Storari was particularly interested in the maintenance of the city's streets and avenues and was also assigned with the construction of the road between Kervan Bridge and Halkapınar Paper Factory. He also prepared the plan of the Kemeraltı bazaar, which was devastated by the 1845 İzmir fire (Arıkan, 2001). Following these successful works, Storari was commissioned to prepare the city plan of İzmir. The most detailed and parcelized plan of Izmir at a scale of 1/5000 up to that time was dedicated to Sultan Abdülmecid. Engineer Storari was rewarded with 10,000 Ottoman Kurus by the Sultan for this important work. In this plan, especially the parts of the city that were reorganized after the Izmir fire of 1845 are detailed, the city is divided into parcels and all buildings (mosques, churches, synagogues, hospitals, police stations, schools, factories, inns), bazaars, squares and roads are indicated by name.

Ahmet Pristine City Archive and Museum Archive

A Guide to Izmir with Historical Notes prepared by Luigi Storari and published in Italian in Turin in 1857 (Guida con Cenni Storici di Smirne), like the Izmir Plan mentioned above, was dedicated to Sultan Abdülmecid. This plan was reproduced and offered for sale as an appendix in the guide. Storari's 64-page Izmir Guide was written for Western travelers visiting the city. Therefore, it was translated into French, the most popular language of the period, by M. Gerard and published in Paris the same year. The Izmir of the period was of great interest to Westerners. Because it was one of the “multicultural” cities of the Ottoman Empire, it became a crossroads for Western travelers. In the 19th century, İzmir was one of the first places where Western travelers met the East. In the second half of the 19th century, the city was connected to Istanbul and the islands of the Aegean Sea, as well as important European ports such as Piraeus, Marseille, Livorno and Venice, and became a frequent destination for Western travelers. For this reason, the guide was sold in important bookstores in Europe as well as in Izmir. Considering this work of Luigi Storari within the history of tourist city guides in Europe will help us to better understand the subject. The touristic travel guides, which originated with Karl Baedeker's guides published in 1835 and John Murray's guides published in 1836 and became popular especially in the second half of the 19th century, were the starting point of Storari's work. These guides are usually 50-60 page booklets written in an objective language, giving practical travel information to the reader/traveler, introducing the city to be visited and providing a city map in the appendix.

Luigi Storari's Izmir Guide consists of an introduction followed by 3 chapters. The author includes the following sentences in the introduction of his work:

“While a city map of Izmir is being printed for the first time, I believe that it is necessary to include a travel guide that reflects the geographical and archaeological features of Izmir and its environs and discusses its historical process. This travel guide, I hope, will be of interest to the people of Izmir. It will also be a very useful book for foreigners who come to this beautiful Asian city to see the ancient ruins, which still arouse curiosity and admiration despite the passage of centuries, and which are the memory of historical events.”*

*Storari's Izmir Guide was translated from the original Italian into Turkish by Prof. Dr. Recai Tekoğlu. See (Ersoy, 2020).

The first part of the guide describes the historical events that took place from the foundation of Smyrna until the second half of the 19th century, when the book was written. Here it is noticeable that Storari has conducted his research on the history of Smyrna in great detail. The author has studied the works of ancient writers such as Strabo, Hipponax, Herodotus and Pusanias and commented on them with quotations. In addition, the information he provides about the Turkish period of Smyrna is accurate, although very brief. After this, he explained the earthquakes of Izmir in 1688 and 1788 according to the documents he found in the French Consulate. According to this, the earthquake in 1688 started from the Sancak Castle across the Gediz River and reached the city from there. The castle was destroyed up to its battlements, more than three quarters of the city was devastated and thousands of people were killed. Only three of the city's mosques survived. The earthquake of 1788 was just as effective as the previous one, but the fire that followed the earthquake destroyed the entire city in a terrible way.

The second section begins with two lines from Italian poet Carlo Macau's poem to Izmir:

“On the one hand you have landed beyond Pagos, on the other hand the sea and Meles surround you”.

According to Storari, only these two lines provide a complete geographical description of the city. Izmir is beautiful when seen from the sea. The view from the old castle on the summit of Mount Pagos is even more beautiful, he concludes the opening sentence of the second part. The second part consists of two parts. The first part depicts Modern Izmir, i.e. Izmir of the 1850s, and the second part depicts Ancient Izmir. The second part, which describes Ancient Izmir, and the third part, which describes the surroundings of Izmir, are subdivided as a five-day sightseeing trail. The author mostly talks about ancient ruins and begins his sentences with the word ’we’ as if he is traveling with them in order to attract the reader/traveler. In modern Izmir, in the early second half of the 19th century, Turks and Jews lived in the higher southern neighborhoods. Christians, on the other hand, settled in the lowland area up to Bornova Bay. To the east, the Meles River irrigates the beautifully planted gardens that supply the city with vegetables and fruit. As an engineer, Storari also noticed some flaws in the Izmir of this period. The city had neither an arsenal nor a harbor. It has no bridges. There were no roads providing transportation between villages and towns. There is no stock exchange. There is no vocational and art academy. Sewage channels were completely neglected as they were in Strabo's time. There is no city lighting. The city beautification society and highway engineering still do not exist. According to Storari, it is possible to divide Izmir of the 1850s vertically into two triangles. The slice irrigated by the Meles stream was used for agriculture, while the other slice, in the direction of the Gulf of Izmir, was full of factories and the city was expanding towards the northeast.

According to Storari, despite all these negativities, thanks to the efforts of Ali Nihat Efendi, under whom he worked between 1851 and 1854, regular and sufficiently wide avenues began to be created in the city. However, their surfaces were not in good condition either. Therefore, there were not many horse-drawn carriages in the city at that time. There are almost no squares, promenades and places of entertainment. In this chapter, the author also mentions the Turkish houses in the city. These are made entirely of wood. From the outside they look like a monastery. From the inside they resemble a tent. In the center there is a large quadrangular, sometimes octagonal, living room. It is extended towards four different facades. A door in the center of the other four wings provides access to four separate rooms. Large mansions are divided into haremlik and selamlık. Almost all of them have fountains. Storari is very positive about the freedom of religion in the city. Especially the Catholic community in the city was given great freedom of belief. The city is rich in schools and each community has its own school. This cosmopolitan structure of the city increases the number of languages spoken in İzmir. In addition to Turkish newspapers, European, Greek and Armenian newspapers were also published in the city. According to the author, one of the most common things you can look for in Izmir is to find people who speak at least three languages. It is not uncommon to find people who speak five or six languages. According to the author, while Italian used to be the most widely spoken foreign language, later, as the Jesuits gained power in France and spread eastward, French became the language of balls and society. The commercial and diplomatic language is still Italian. While Storari describes important buildings in the city such as the Greek Hospital, Hisar Mosque, Vezir Han, Sarı Barracks and the steam mill at the westernmost end of the barracks, he also mentions the Armenian Church in the city. Critically, he mentions the inexperience of the architect who designed the building, the fact that the building could not be placed on a solid foundation and could only be completed in 1854, and that it could already be demolished. As for the information given by the author about the administration of the city, Izmir was governed by a Pasha who served as governor. He also underlines that all foreign countries had a consulate in the city. At the end of the second part, the author reiterates that agriculture, art and science were neglected in the city, but he also states that the city was developing rapidly and that it was no longer possible to recognize the Izmir of the 1800s in 1855.

In the third part of his work, Storari describes the places and ancient ruins in the immediate vicinity of Izmir. These are the Kervan Bridge, the Temple of Meles, the Halkapınar Diana Bath, the Bornova Plain and the villages of Bornova and Kokluca. In this section, the author continues to visit the ancient ruins with references to contemporary travelers such as Spon, Tournefort, Pococke and Chandler who wrote about Izmir.

We believe that Engineer Luigi Storari, who came to Izmir in the period beginning with the Tanzimat Reforms and undertook important tasks here, has other works in Izmir that have not yet been revealed. We firmly believe that with in-depth research in local and foreign archives, not only Storari's works, but also the works of all western architects and engineers in Izmir in the Tanzimat and post-Tanzimat period can be revealed.

Arikan Z. (2001). Storari's Kemeraltı Plan. Izmir City Culture Magazine, 4, 76-80.

Berkant, C. (2017). Italian Engineer Luigi Storari (1821-1894) and Izmir Guide with Historical Notes. Çeşm-i Cihan, E - Journal of History, Culture and Art Research, 4 (2), 2-13.

Ersoy, A. (Ed.). (2020). Luigi Storari and Izmir Guide, Izmir Metropolitan Municipality City Library.

Yerasimos, S. (1996). Quelques Éléments sur l'ingénieur Luigi Storari. Architettura e Architetti Italiani ad Istanbul tra il XIX e il XX Secolo, 117-123.